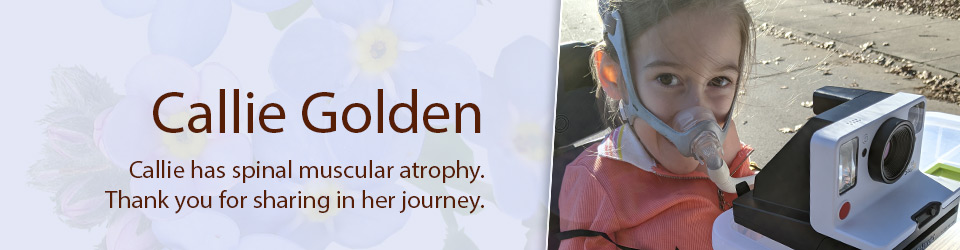

Callie is now a third grader.

Callie with her tea set at the beach.

Over the summer, she spent her mornings eating waffles with syrup and toast drizzled with honey. She played Minecraft on the PlayStation with her brothers, went to Vacation Bible School, and played on the beach. I’ve also been reading aloud the Harry Potter series to Callie and her brother Peter. With a homemade wand in her hand, she goes back and forth pretending to be Hermione one minute, then Harry the next.

Over the summer we also learned that Callie has received approval for Spinraza, the new and only treatment available for SMA. The drug is administered as an injection into the spine and Callie would receive the injection several times a year for the rest of her life. We’re hoping to start her injections within the next couple of months. There’s no guarantee the medicine will help, so it’s been a difficult decision to make.

Nathan and I are always weighing the pros (potentially seeing a mild increase in Callie’s arm strength) against the cons (an invasive procedure that will require sedation) when we make medical decisions for Callie. We plan to move forward with the treatment because we think there’s a chance it can improve Callie’s comfort and quality of life.

Snack time at Vacation Bible School.

One thing that has had a significant impact on Callie’s level of comfort is the rapid progression of her spinal curvature, known as scoliosis. Although we know Spinraza cannot reverse the damage SMA has already done to her body, we recently got X-rays of Callie’s spine in order to examine the extent of the damage, as well as determine if there’s any kind of intervention that might allow Callie to benefit more from her Spinraza treatment.

We learned that a spinal curvature of greater than 40 degrees is considered severe. Callie’s curvature is 120 degrees. After discussing a number of scenarios with a pediatric orthopedist, who regularly cares for SMA patients, we had basically one course of action: Admit Callie to the hospital and infuse nutrition straight into her veins to try to improve her nutritional status. We’d then have to use halo traction, a procedure that would involve putting 12-15 screws into her skull, attaching them to a circular metal device above her head — the “halo” —with weights behind it to slowly stretch her muscles and spine in preparation for surgery.

Then, if she tolerated the halo traction and managed to gain weight, she could have back surgery with a tracheostomy placed. When we told the orthopedic surgeon we’d already decided against Callie having a tracheostomy, he said if we didn’t consent to a tracheostomy, he wouldn’t do the surgery. Based on his experience and research, she wouldn’t be able to come off the ventilator after surgery, so without a tracheostomy for breathing, he would be performing a surgery he knew would be fatal.

Nathan and I have done plenty of research on this topic, so none of this surprised us. But it was still very hard for me to hear. In the few months leading up to this orthopedic appointment, I had allowed my mind to drift towards things that might magically come true, thanks to Spinraza. I’d allowed myself to hope that Callie might even walk one day. Sitting there in the doctor’s office sealed what I already knew to be true — this dream of Callie’s, of our entire family, was impossible.

I’ve had to do my best to let go of that and move forward. After all, as Albus Dumbledore told Harry Potter, “It does not do to dwell on dreams and forget to live.”

Comments have been disabled.

Or would the treatment only slow the progression of her condition, requiring her to endure more pain with little or no benefit to her quality of life? There are no simple answers.

Or would the treatment only slow the progression of her condition, requiring her to endure more pain with little or no benefit to her quality of life? There are no simple answers.