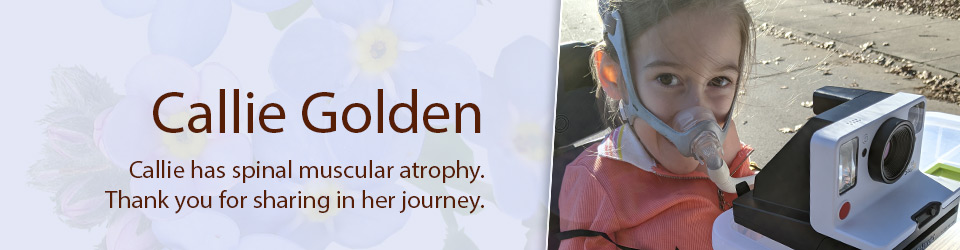

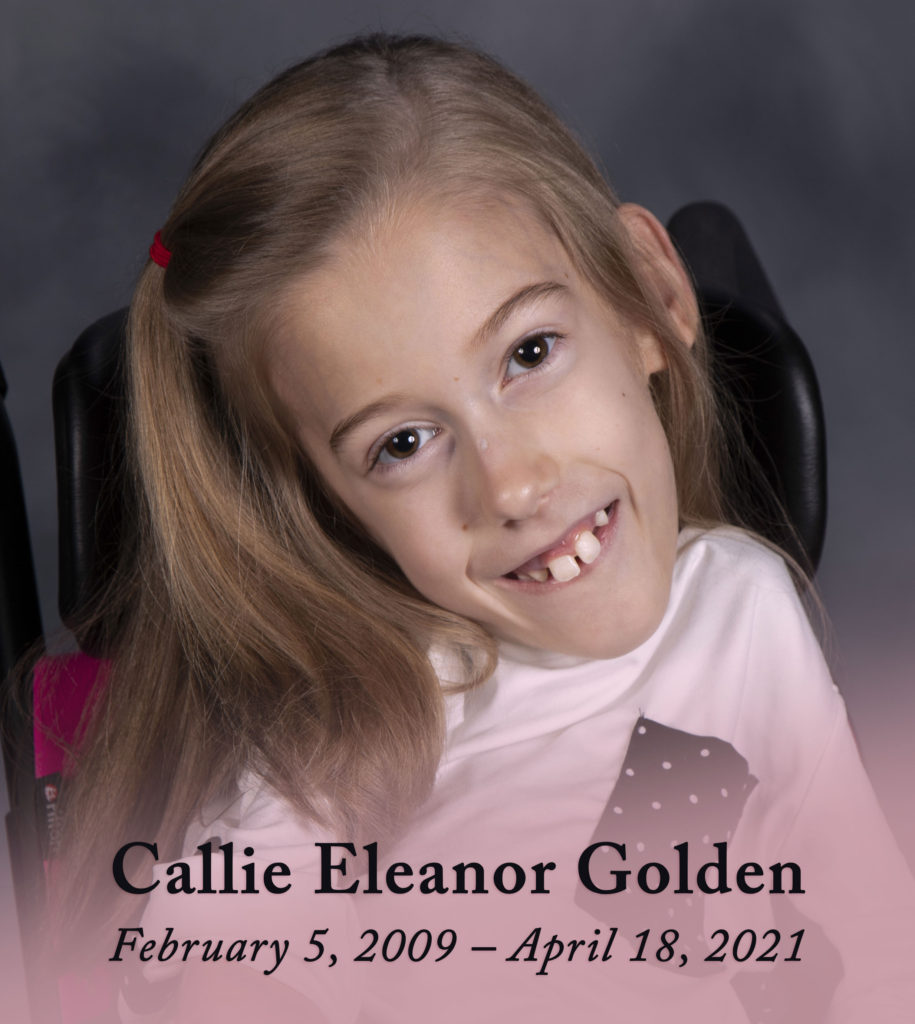

Callie died on Sunday morning, April 18, 2021. The following blog post shares her final two weeks with us. This post published on July 18, 2021, three months after Callie’s death.

A two-week notice

This story begins in late March. Callie and her 13-year-old brother, Peter, were on spring break. We decided to visit Charleston, S.C., to see our 18-year-old son, Ezra, who had just started a temporary job there.

We had a great time. We stayed near the historic part of town and enjoyed walking around and taking pictures. We visited Ezra and also got together with other family and friends in the area.

That trip felt like the beginning of a new chapter. Our oldest two boys were more or less grown all of a sudden. We had become a family of four — Callie, Peter, Christy, and I. On the way home we talked about all the other trips we could take to visit our older sons and other family and friends.

Yes, Callie had been very sick several times in her life. She’d been close to death more than once. Every day she relied on medical equipment to breathe. Caring for her had become a full-time job for more than one person.

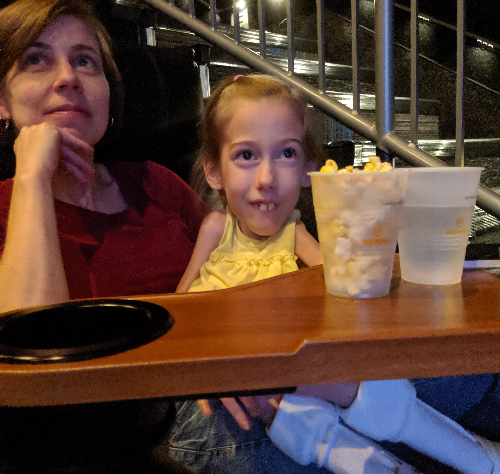

But no medical challenge had ever diminished her love for life. Inadvertently, as the years passed, we’d started to assume Callie would always find a way to keep going. She always had, for 12 years, and we were excited about the next 12 years of life with her.

We got home from Charleston on Wednesday, March 31, and spent the next couple days getting back into a regular routine. On Friday of that week, Callie said she wanted to talk to us alone. This wasn’t too uncommon. As a 12-year-old, Callie sometimes had things she wanted to discuss without Peter listening.

She told us she was tired, and we affirmed her feelings, reminding her of the long trip we’d just taken.

“No,” she said, “I mean too tired for life.”

Again we jumped in with solutions. The pandemic had kept us home for about a year. Callie was always so sociable. Being home so much was particularly tough on her. We offered to visit some of her favorite places, to go for more walks, to find more fun things to do. With state restrictions lifting and vaccines rolling out, we’d be back to normal life soon enough.

She said, “There’s nothing you can do to help this.”

She’d gotten our attention.

“I want to say it but it’s too sad,” she said. She meant it would be too sad for us. We encouraged her to tell us what was on her mind.

“I feel like it’s time for me to die,” she said.

We listened. Callie made it clear her main concern was whether we’d be OK if she died. We promised if she went to Heaven, whenever that happened to be, we’d miss her terribly but that we’d be OK.

Not telling anyone

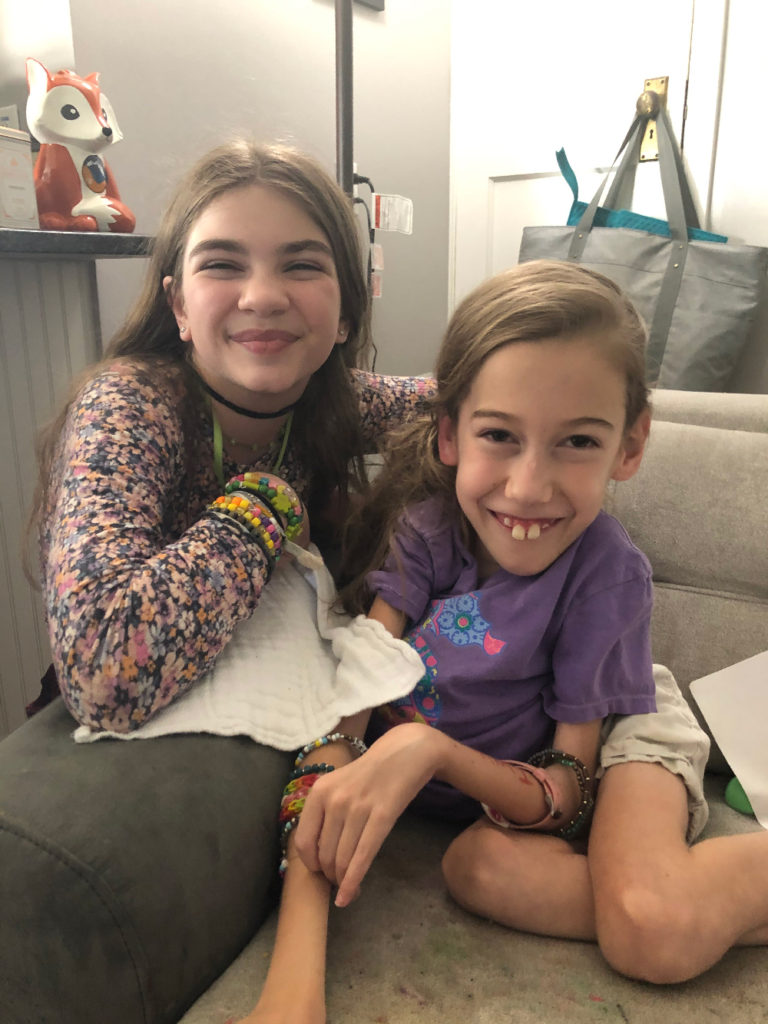

Callie insisted we not tell anyone the way she felt except for her brothers and her best friend, Gillen.

Her brothers had shared so much of Callie’s journey with us. They would be surprised, though not shocked, by this development. But maybe you shouldn’t text this information to Gillen, who was 11, we said. At least not yet. Not until we knew a little more about what was going on.

Callie was insistent. She said she had to tell Gillen or she couldn’t relax. She couldn’t go to Heaven without talking to Gillen first. So Christy called Gillen’s mom who re-arranged their family’s entire day, making time for a visit.

The two girls cried together but were laughing again soon enough as they played video games and shared jokes as usual. Seeing them together made us think maybe Callie had been feeling lonely and simply needed to see her best friend. Maybe life would be back to normal soon after all.

But Callie never wavered in her certainty that her time with us was coming to an end. Not that day and not in the days ahead.

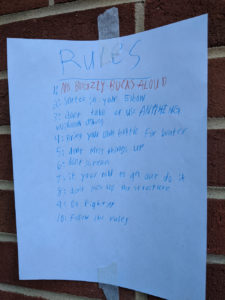

We asked Callie if we could tell her grandparents, her teachers, or any of her other friends. She was against it. She didn’t say why, exactly, but now we think she wanted to spend her last weeks doing the things she enjoyed without a lot of extra attention. This was, after all, how she enjoyed living her life.

As that weekend progressed we went for walks and ate good food. Christy fried some shrimp which was one of Callie’s all-time favorites.

At times, she’d take on a far-away demeanor. Her voice would sound weaker. She’d want to take off her bi-pap mask which was essential for her breathing. She mentioned seeing angels and Heaven but she couldn’t describe what it all looked like.

“Anything you see on TV is ridiculous,” she said.

Letting go of earthly things

Callie lived her normal life over that weekend, which included Easter Sunday. We walked (power-chaired) over to the track and ballfields behind the high school near our house.

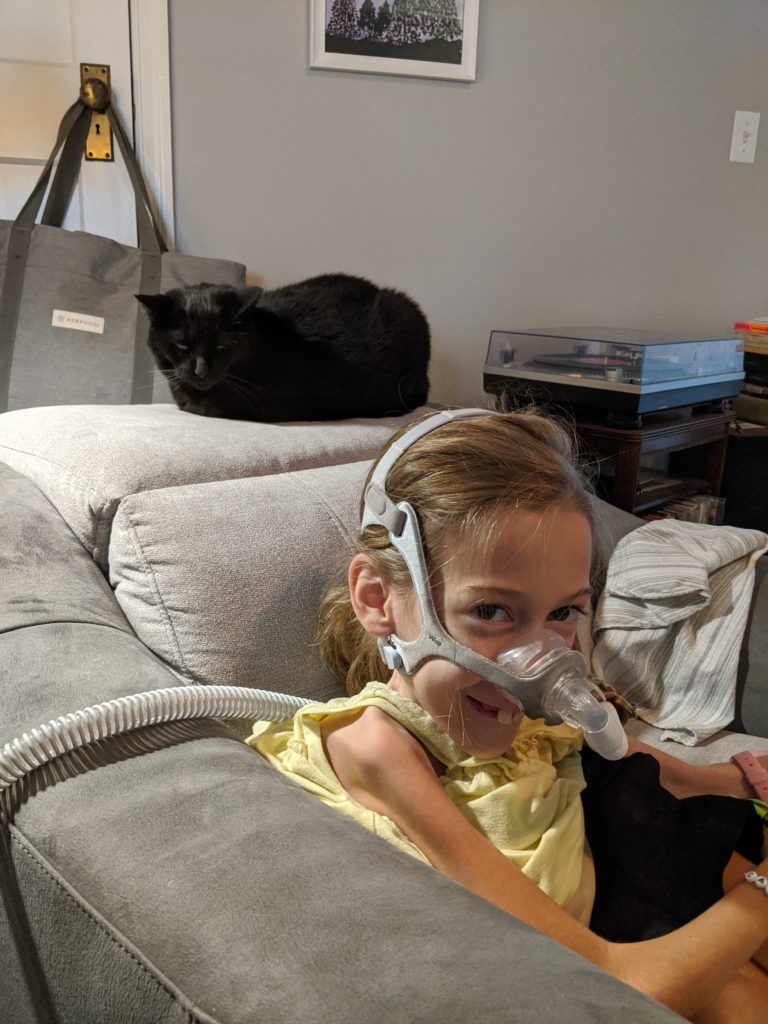

Callie wanted her bipap breathing machine off during long stretches of this time so she could smell the world and feel more a part of her surroundings as she circled the quarter-mile track. Then, back at home, she’d want to lie down and would seem contemplative. Yet she always came back to herself and wanted to get back up.

By Monday, the day after Easter, Callie had become confused. She felt ready for whatever was next. But her body, though damaged and twisted, showed no signs of letting go. Callie wondered if she’d been wrong to think she was ready.

Christy called our Hospice nurse. Hospice of the Piedmont, along with the pediatric palliative team at Brenner Children’s Hospital, had guided us through several complex illnesses over the years.

The nurse had an answer for this particular phase of life, too. She called it a lag time — a period in which the body hasn’t caught up with the spirit’s awareness that death is near. This explanation satisfied Callie’s concerns.

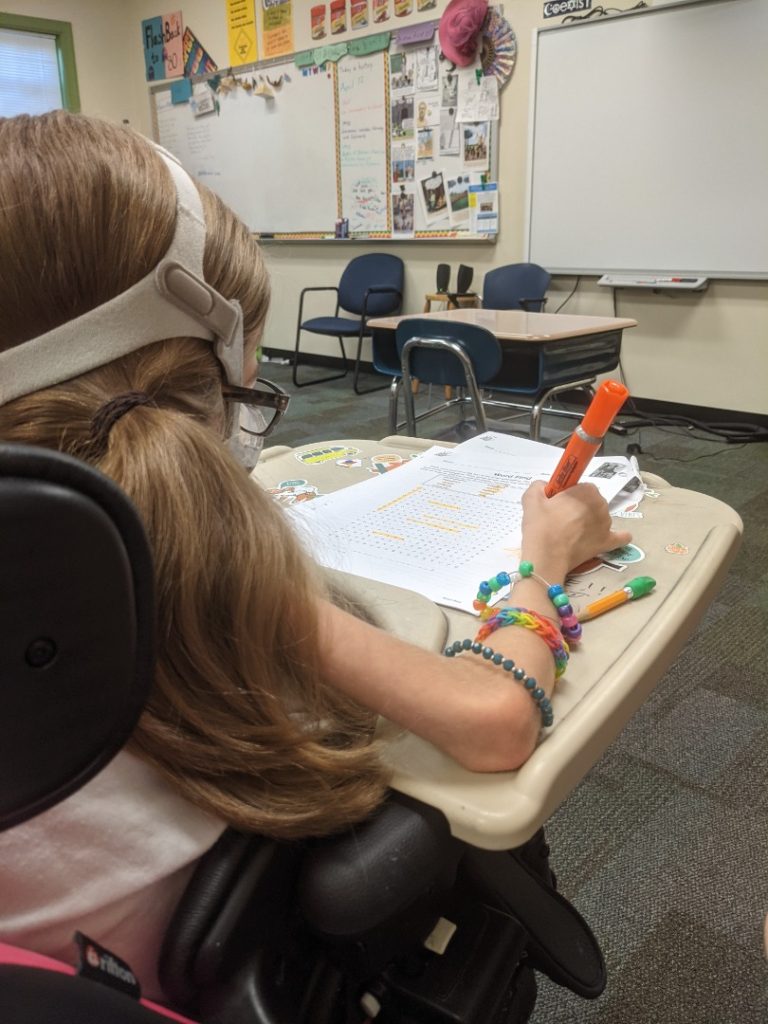

School returned from spring break that week. Callie wanted to go back but could attend only sporadically. She did make it through the entire day on Friday, which was one of her goals for the week. She loved going to school.

Our oldest two sons came home that weekend: Ezra from Charleston and Isaac from his trade school west of Nashville, Tenn. They’d FaceTimed but still wanted to visit, even though none of us really felt like Callie would be leaving us all that soon.

The following Monday morning, April 12 — six days before she died — Callie went to school for the last time. Her school nurse was on a different assignment so Christy went with her that day. Within a couple hours, it was clear Callie was too exhausted to carry on at school any longer. Christy told her it was OK to go home.

That afternoon, back at home, Callie agreed to let us tell her teachers and principal why she wouldn’t be back to school. We couldn’t offer very much specific information. The only certainty we had was Callie’s certainty. She calmly assured us she was almost finished with her life.

I didn’t believe her, at least not fully, until that evening. We’d gotten some food from Subway which included Callie’s favorite chips, Barbecue Baked Lays. As we ate, Callie was reminiscing about a summer evening a couple years before. On that night we’d walked Peter to his swimming lesson and then stopped at the Subway across the street from the pool.

Callie’s story prompted me to say something like, “We’ve had some fun times, haven’t we?”

“Yes,” she said. “We did.”

More than her descriptions of the angels she’d seen taking other people to Heaven, Callie’s use of past tense — “We did” have some fun times instead of “We have” — told me she was letting go of the life she’d lived with us.

Beginning the dying process

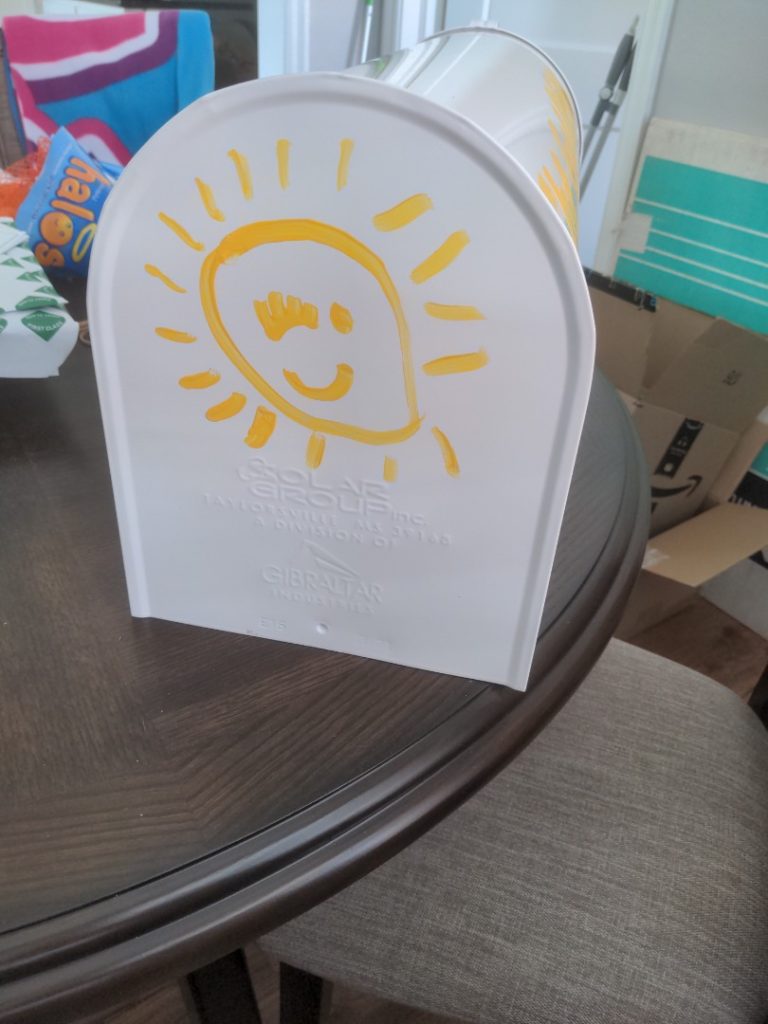

Callie had always wanted to paint a mailbox for our yard. Probably because she noticed other nice mailboxes on our walks around the neighborhood. Someone from the post office had installed our mailbox when we moved in. It was gray and simple.

I put off this project, month after month and year after year. With so much else to do, replacing a mailbox never made the cut.

Callie’s best friend, Gillen, has an older brother whose high school required a service project before graduation. He asked if Callie needed anything, and we thought of the mailbox idea.

So on Tuesday evening, April 13, Gillen and her mom dropped off a new mailbox and visited with Callie for a few minutes. Gillen and her family were still among only a handful of people who knew how Callie had been feeling during this time.

At bedtime that night, Callie said she’d like Christy to cook sweet-and-sour meatballs with homemade, baked macaroni and cheese, one of her favorite meals, the next day.

The next day was Wednesday. Peter left for school and we got the mailbox and some paint out for Callie. She had almost no energy left to sit up. She needed both hands to hold her paintbrush. But she managed to paint “The Goldens” in yellow paint and our house number in big black numbers.

Callie loved to paint, and her artwork often included a bright, smiling sun with one eye winking. She was nearly out of energy, but she put her trademark winky sun on the back of the mailbox so we could see it from our front windows.

After painting, Callie was ready to lay back down, and I decided it was a good time to run a few errands since she’d likely go to sleep. As I backed down the driveway, Christy called and asked me to come back in. Callie was still in bed but was upset, saying everything hurt. She couldn’t explain the problem beyond that.

With Callie so agitated, afraid, and unable to understand why she felt so bad, we reached out to Hospice. Callie’s nurse, Nancy, came over. Dr. Maike Copeland, a Hospice physician who knew Callie well, also stopped by.

They suspected Callie was experiencing terminal agitation, a common end-of-life occurrence. We asked lots of questions, and they said Callie’s prognosis was uncertain.

We were also in touch with the palliative team at Brenner Children’s. This team, led by Dr. Savi Nageswaran and nurse Andrea, had been equally helpful over the years.

We asked if Callie’s bipap was causing more harm than good. We learned there was nothing we could do to stop Callie from dying. She was transitioning into the dying process. Keeping her comfortable — whether on bipap or off — was our top priority.

After a few hours, Callie managed to calm down and get some rest.

A special meal

Christy cooked the dinner Callie requested and made her a plate, cutting the meatballs and macaroni. Callie had always insisted on sitting up and feeding herself. This night was no different.

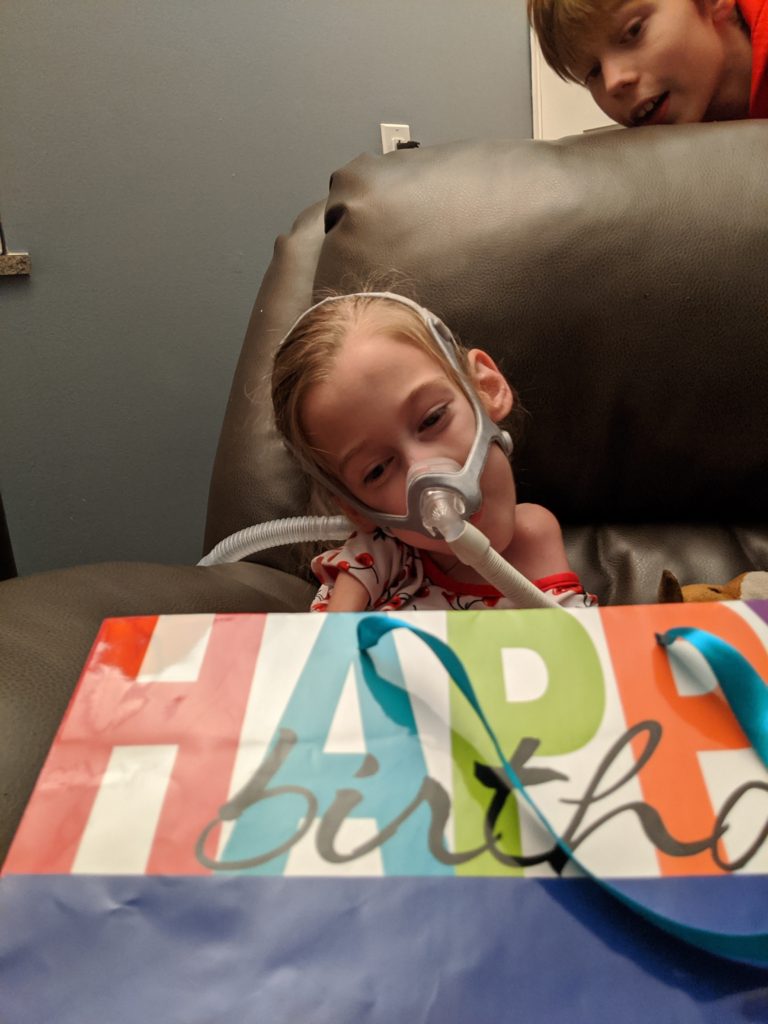

This night resembled any other evening in our den in other ways, too. Callie sat in the special recliner we’d bought for her. She referred to the chair as her “nest” because she kept it filled with her things — drawings, collections of small toys, books, pencils, and anything else she wanted nearby.

Callie and Peter watched TV together. They started an episode of “Full House,” the sitcom from the late 1980s. Callie loved these little joys of life: Eating good food, spending time with family, watching TV shows.

She couldn’t eat, though. She didn’t have an appetite. She wanted to lay back down. As we put Callie back in bed, Christy wished out loud that she’d cooked sooner, maybe for lunch instead of dinner, so Callie could have enjoyed her meal.

Callie rested well for several hours that night. At about 2 am she woke up very thirsty and drank most of a cup of water — a lot by her standards. She mentioned being hungry but wanted to wait until the morning to eat.

At 4 am she woke up again. This time, she couldn’t wait to eat. I got her up. Christy heard the commotion and came to help us. Callie wanted a bowl of Honey Nut Cheerios, which she ate energetically. A few bites into the bowl of cereal, Callie remembered the meatballs and baked macaroni from the night before.

She wanted her plate reheated. She let us help her eat, and she enjoyed her special meal.

I wondered, once again, if all this talk of dying was just a big misunderstanding, an exaggeration. If her appetite was back, maybe she’d be feeling more like herself as the day went on.

Her hunger satisfied, Callie drifted back to sleep.

Three days holding her

We spent the next three days holding her. We’d take turns, a few hours at a time.

Callie slept. She moaned some on the first day, Thursday, April 15. We kept her on her bipap machine that day even though the machine’s air pressure seemed to be agitating her at times. With the Hospice nurse’s help we learned how to use medicine to keep Callie comfortable.

We lowered the air pressure on her bipap, but the machine still seemed to be impeding her rest. By Friday the machine was clearly too invasive, so we stopped using it, and she continued to rest well without it.

You’d think three days spent on a couch would creep by, but they didn’t. Each day passed too quickly. Throughout those days we told her how much we loved her and how well she was doing. Peter was a constant presence, too. He reassured Callie and told her what a good sister she was.

Once, she looked up at me and said, “Are you OK, Dad?” For those couple seconds it seemed like she was back with us, but then she drifted away again.

She wanted both of us equally. It had always been a running joke around our house that Callie preferred me to hold her. Lots of times, when she needed something, we’d ask whether she wanted Mom or Dad.

She’d normally answer, “No offense, Mom,” and we all knew what that meant. She wanted me to help her.

But on these days she wanted us both, and neither of us wanted to give up our turn too soon.

Whoever wasn’t holding her took care of details around the house. Christy washed every item of Callie’s clothing and sheets that she could find so Callie could have all her favorite outfits to choose from. I kept trying to get some work done. Taking a break would require acknowledging what seemed to be happening.

The Hospice nurse visited each day. One of our pastors stopped by, too, after Callie agreed to share what was going on.

We also heard from our longtime family friend, Sandy. Between busy lives and the pandemic we hadn’t been in touch with Sandy and her family lately. But we’d continued to share a set of hair clippers for boys’ haircuts, passing it back and forth as needed. Sandy needed to pick up the set from our house.

We asked our pastor to drop off the hair clippers at Sandy’s house. We knew Sandy would find it odd if our pastor showed up with a set of hair clippers, so we asked our pastor to let Sandy know what was going on with Callie.

Soon after, a bag of Chick-fil-A food materialized at our front door right after we saw Sandy’s van driving down the block. We ate, not knowing we’d even been hungry.

Though she was only occasionally conscious, Callie kept to her routine. In the mornings she’d get out of bed and we’d move to the couch. In the evenings we’d move everything back to her room for the night and tuck her in.

Telling family

Saturday night, as we put Callie in bed, she was so much weaker than I’d ever seen her. She could still communicate with us through little sighs and nods and by fluttering her eyes a little.

As a nurse, Christy has cared for dying patients. She recognized something in Callie’s breathing and appearance that left no doubt Callie’s life was nearing its end. It seemed possible Callie wouldn’t make it through the night.

At this point we still hadn’t told Callie’s grandparents or other extended family what was going on. Callie had asked us not to, and she hadn’t told them either, despite being on FaceTime and having opportunities to do so.

On this Saturday night we told her we really needed to tell her grandparents. Callie nodded her consent. We got both sets of grandparents on speaker phone, one after the other, and quickly filled them in.

Over the phone, Callie got to hear how much she was loved and how much her life had touched other people — people she didn’t even know. She heard how proud everybody was of how she’d lived her life.

She heard her 2-year-old cousin Olivia’s voice and fluttered her eyes in recognition. She adored Olivia. She heard Olivia’s mom promise to tell Olivia all about Callie when she got older.

Callie’s insistence on not sharing suddenly made more sense. She’d wanted to live her normal life as long as possible. Callie wasn’t outwardly affectionate. She got to hear how much she was loved without having to participate in the conversation.

It was a hard hour. We turned off the lights and neither of us wanted to leave Callie’s room. I encouraged Christy to go to bed so I could do what I was in the habit of doing, taking care of Callie at night, one more time. She did, but I don’t think she slept much, if any.

At first Callie’s heart rate was way too fast and her oxygen level was too low, and I didn’t think she could make it until the morning. After midnight, though, she settled into some of the best vital signs she’d had in days.

During those hours she would occasionally call out, “Hey, Dad.” I could barely hear her. I never knew exactly what she needed but would try out a few things, repositioning her head on the pillow or offering her a sip of pink lemonade which she could take only through a small syringe at this point. Maybe I guessed correctly since she’d settle back into sleep within minutes.

At 3 am Christy came up the hall to relieve me and I slept a couple hours. Callie was resting comfortably, and I knew she could make it through the night.

Final moments

When I got up Callie was still resting comfortably as Christy cared for her. Christy was wearing a sweater that Callie loved. Even though it was made out of a rough material, Callie had always liked resting against it.

We started to get Callie out of bed, just like we had on the previous days, and I thought we may have yet another day to hold her, back and forth, on the couch.

We didn’t make it out of her bedroom that morning. Callie’s oxygen levels started to decrease. This had happened a few times in the preceding days, but this time her numbers weren’t bouncing back.

I called Hospice to let the nurse on call know what was going on.

We needed some basic medical supplies so Christy had asked her friend Sandy to drop them by on her way to church that morning. Sandy arrived in time to tell Callie goodbye, and she also agreed to stay in case we needed anything else.

Callie’s oxygen level was reading lower than I had ever seen it — below 80, and then below 70. By then, Christy was holding Callie in the recliner we kept in Callie’s bedroom.

Callie asked for me with a quiet “Hey, Dad.” As I held her, the vital signs we’d spent so many years monitoring started to decrease slowly. Her oxygen level kept falling, gently, gradually. Her heart rate began to slow down, just as gradually.

Christy sang that old song “My Girl” which Callie had always loved. When they got to the chorus, Callie would always chime in with her part, just those two words, “My girl.” On this morning when that line came, Callie grunted her part, and we knew she was still with us.

We turned the pulse oximeter off. Its numbers no longer mattered. Callie kept breathing, gently, quietly, more slowly. Then she inhaled and didn’t exhale. Christy and I froze. There was nothing to say or do. We sat still and held Callie. I could still feel a little air moving around in front of her nose for a few more minutes.

Then, the room changed: a feeling that this, even this, was OK. Christy felt the same way. We both looked up, simultaneously, in response to that feeling.

Later, after the funeral, we wondered if what we felt had been Callie turning around to hug us as we held onto the body she’d just left.

Bath and funeral home

The on-call Hospice nurse came in. She listened with her stethoscope and confirmed that Callie had died. It was 9:45 am Sunday, April 18, two hours after she’d gotten up. The nurse called the funeral home. Christy started calling family members, starting with our older two sons.

I got Callie’s little body in the bath because she’d had no energy for one the previous couple days. With the Hospice nurse’s help, I used Callie’s most recent favorite soap which smelled like coconuts. We also used her favorite shampoo and conditioner.

Christy and I got Callie dressed in a teal shirt and dark Capri pants which she’d asked for just two weeks earlier but had worn to school only once. We put her pink socks on her feet.

During this time Peter was giving Sandy a tour of the yard, and we were glad she had stopped by. Christy dried Callie’s hair and put up her side ponytail, which had been her most recent style.

With nothing left to do we sat on the couch and held Callie, waiting for the funeral home to arrive. Her body still felt the same as it had when she was alive.

When the two men from the funeral home came in with a gurney, Christy asked them not to rearrange Callie after they took her. Callie’s legs didn’t stretch out and she had to have her pillows arranged just so to keep her from rolling over since her spine had rotated so much. We’d had this same conversation with nurses prior to several surgeries over the years.

The two men from the funeral home were patient and kind. Christy was holding Callie when it was time for her to go. I took her and laid her on the gurney, and we arranged her properly.

By this time Peter was back inside. He was explaining to the funeral home employees how special Callie was and how much he wished they could have met her.

They took the gurney out the front door and down our front steps. When Callie reached the bottom of the steps, beyond the shadow of our roof, the sun lit up her face.

What’s next?

Three months have passed. Our lives are totally different. We’d shaped everything we did and every choice we made — big and small — around Callie’s needs.

Those habits seem hard to break. We still reach for her favorite foods in the grocery store before realizing. We still plan ahead as if one of us needs to be at home or close to Callie’s school just in case.

We promised Callie we would be OK, and we will, but OK doesn’t mean we don’t miss her.

We worry most about Peter, and we’ve noticed others seem to feel the same way. When the kids at Callie and Peter’s school learned about Callie’s death the following Monday, Peter’s well-being was the students’ top concern.

He’d never known life without Callie, so there was good cause for concern. Overall he’s been doing well. He’s been overwhelmed by sadness at times, but he’s also been able to enjoy his life.

Our two older sons are doing OK, too. It’s different for them being away. We’ve noticed it’s been hard when they’ve come home and felt Callie’s absence more directly.

We don’t expect to understand Callie’s purpose or to know what she accomplished in her life. We do know that for 12 years we had the best little girl, a girl whose quiet bravery and love for life gave our lives more meaning.